Introduction

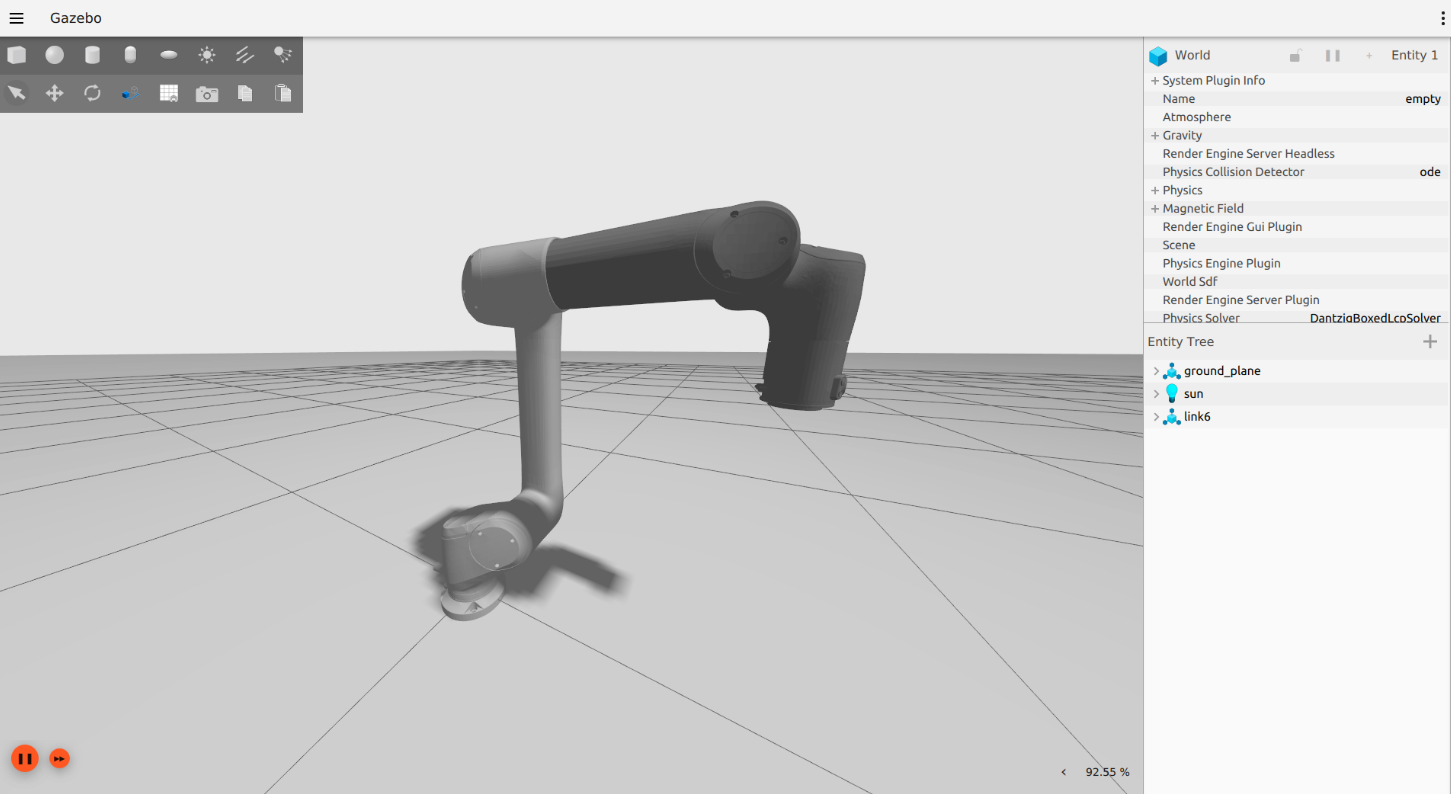

During my internship at Kinova, I worked on the Link6 arm – a 6-DoF cobot that lives in the same ecosystem as a UR5/UR10: strong, fast, and designed to be safe around humans. Under the hood it runs on Kortex3, Kinova’s common software platform for their new robots.

When I arrived, the Link6 exposed a Cortex API that let you send:

- joint velocities

- end-effector twist

…but there was no ROS2 stack on top of that, no standard controllers, no clean way to plug into the usual ROS tools or into any learning pipeline. The first half of my internship was basically:

Turn “here’s a low-level API” into a ROS2-native cobot you can launch, visualize, simulate, teleop, and log.

Building the ROS2 Stack

The first step was just getting a clean workspace layout and wiring Kortex3 into ROS2 Humble:

link6_descriptionfor URDF/Xacro and meshes,link6_driverfor the hardware interface and Kortex3 communication,link6_controlfor ROS2 control configs and controller manager setup.

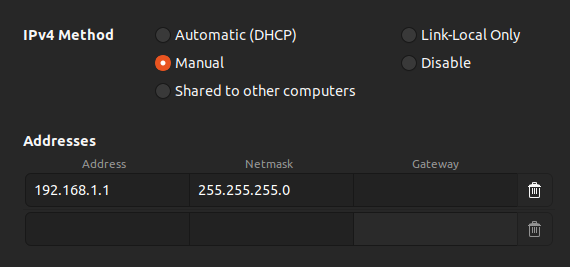

Behind the scenes, the driver talks to the robot over UDP (read) and MQTT (write) on the robot’s default IP (192.168.1.10), while ROS2 sees a normal arm publishing joint_states and TF.

Once the networking is configured and the arm is green, you can bring it up from ROS2 and everything else in the stack “just” sees a robot with:

- joint state broadcaster,

- joint velocity controller,

- Cartesian motion controller,

- optional Robotiq gripper controller.

It’s the usual ROS2 experience, but sitting on top of Kinova’s Kortex3 API.

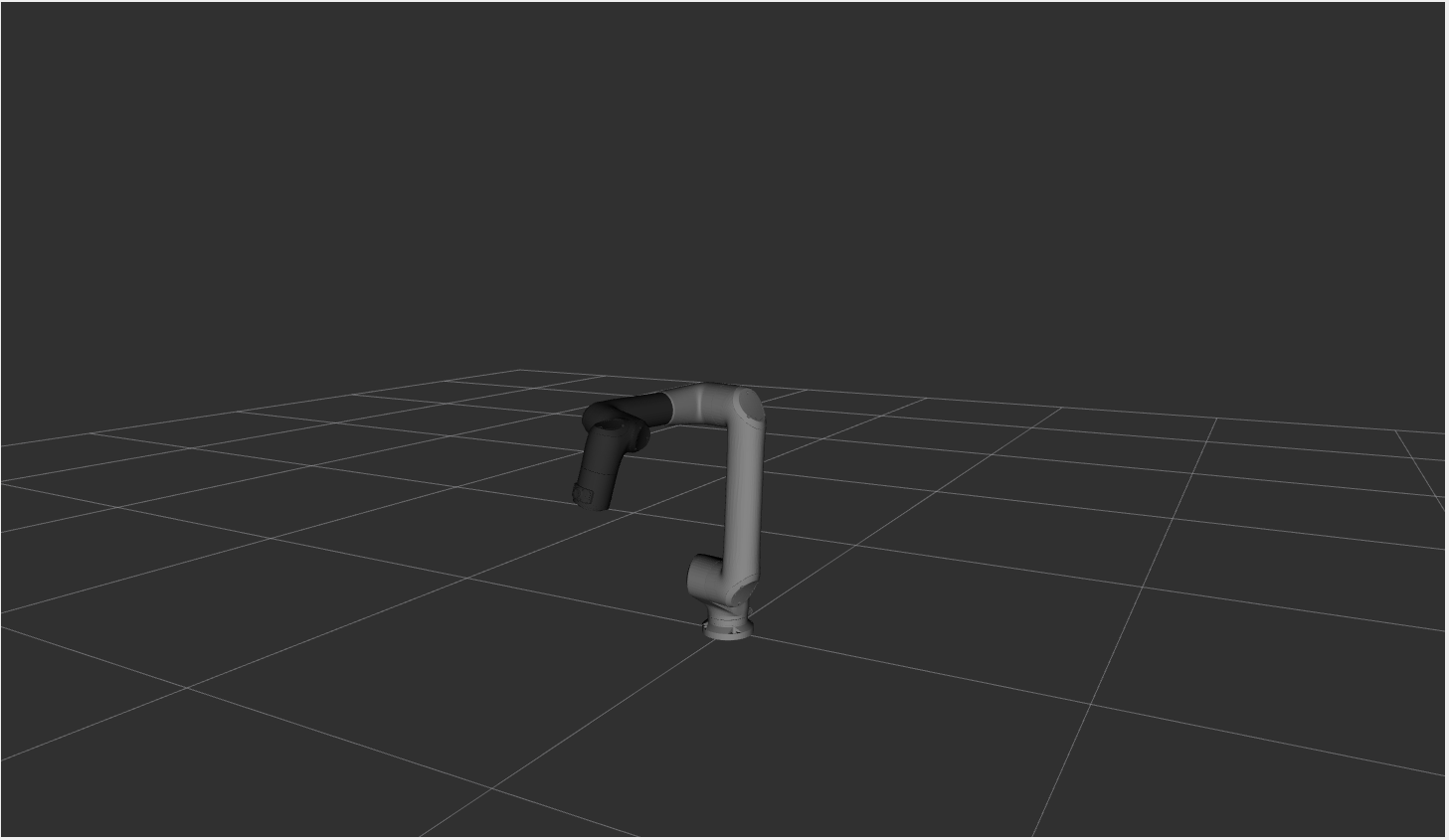

Real & Sim: One Stack

From the beginning I wanted real and simulation to share the same interface. The Link6 stack supports:

- Real hardware bringup (with or without a Robotiq 2F-85), and

- Ignition/Gazebo Fortress simulation using the same description and control configs.

That means:

- Same launch entry point (

link6_bringup), - Same controller names,

- Same topics (

/joint_states,/cartesian_motion_controller/target_pose,/joint_velocity_controller/commands, etc.), - Same TF tree.

So if you prototype something in sim (controller logic, teleop, logging, etc.), you can move to real hardware with minimal changes.

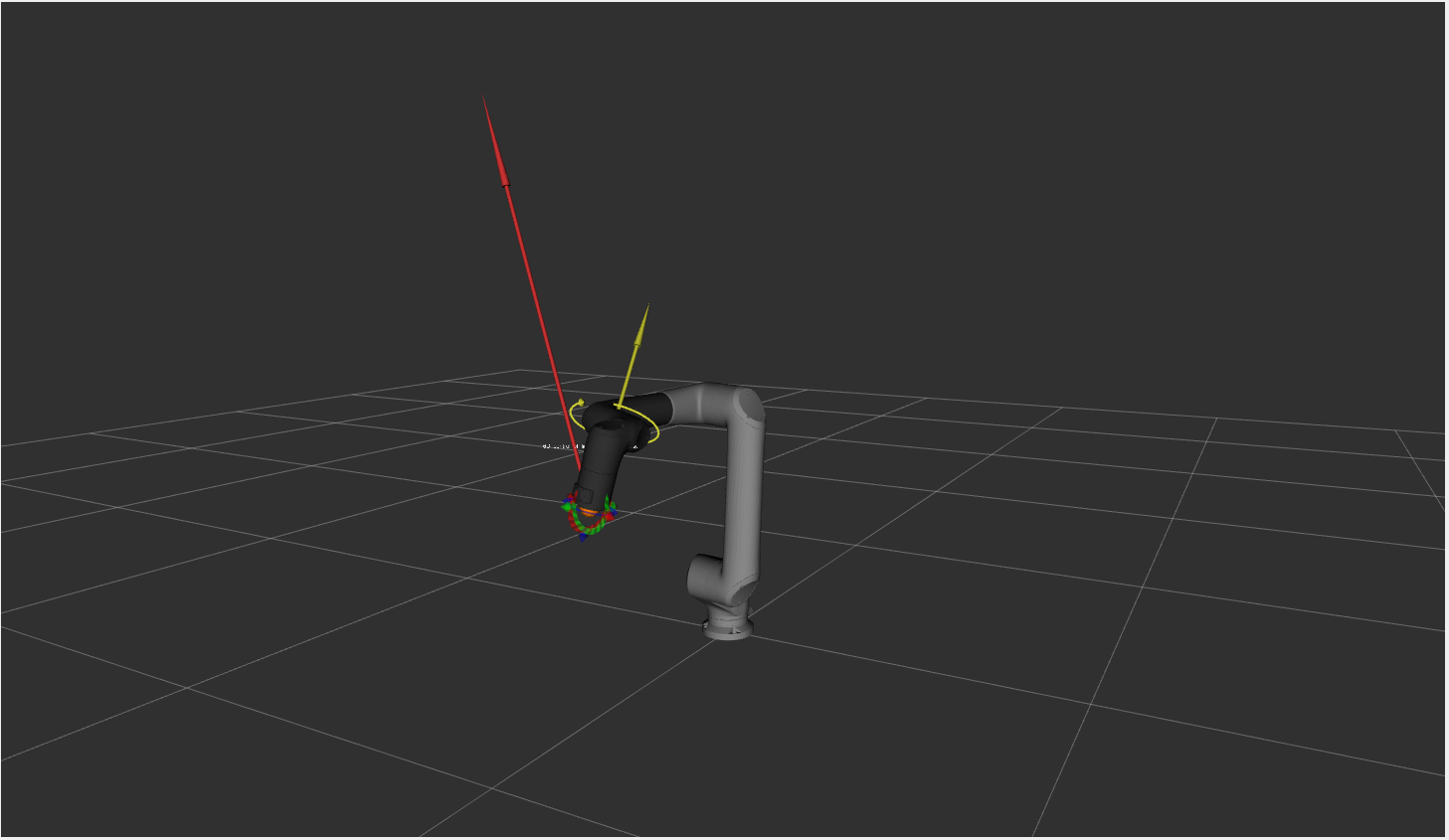

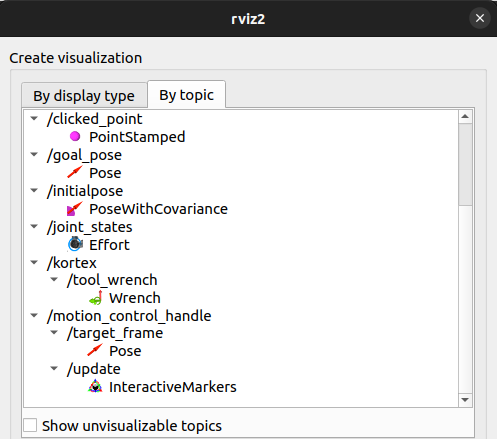

For visualization I ship a ready-to-go RViz config that loads the robot model, TF, interactive markers, and the tool wrench display.

Calibration & Fault Handling

Because this is an actual cobot and not a perfect URDF in a vacuum, calibration matters.

On bringup the driver:

- Pulls the on-board calibration bundle from the arm,

- Expands the nominal URDF to a concrete model,

- Runs a small script to generate a calibrated Xacro,

- Switches the robot description to that calibrated model.

So RViz, controllers, and any kinematic computation use the same calibrated geometry the robot uses internally.

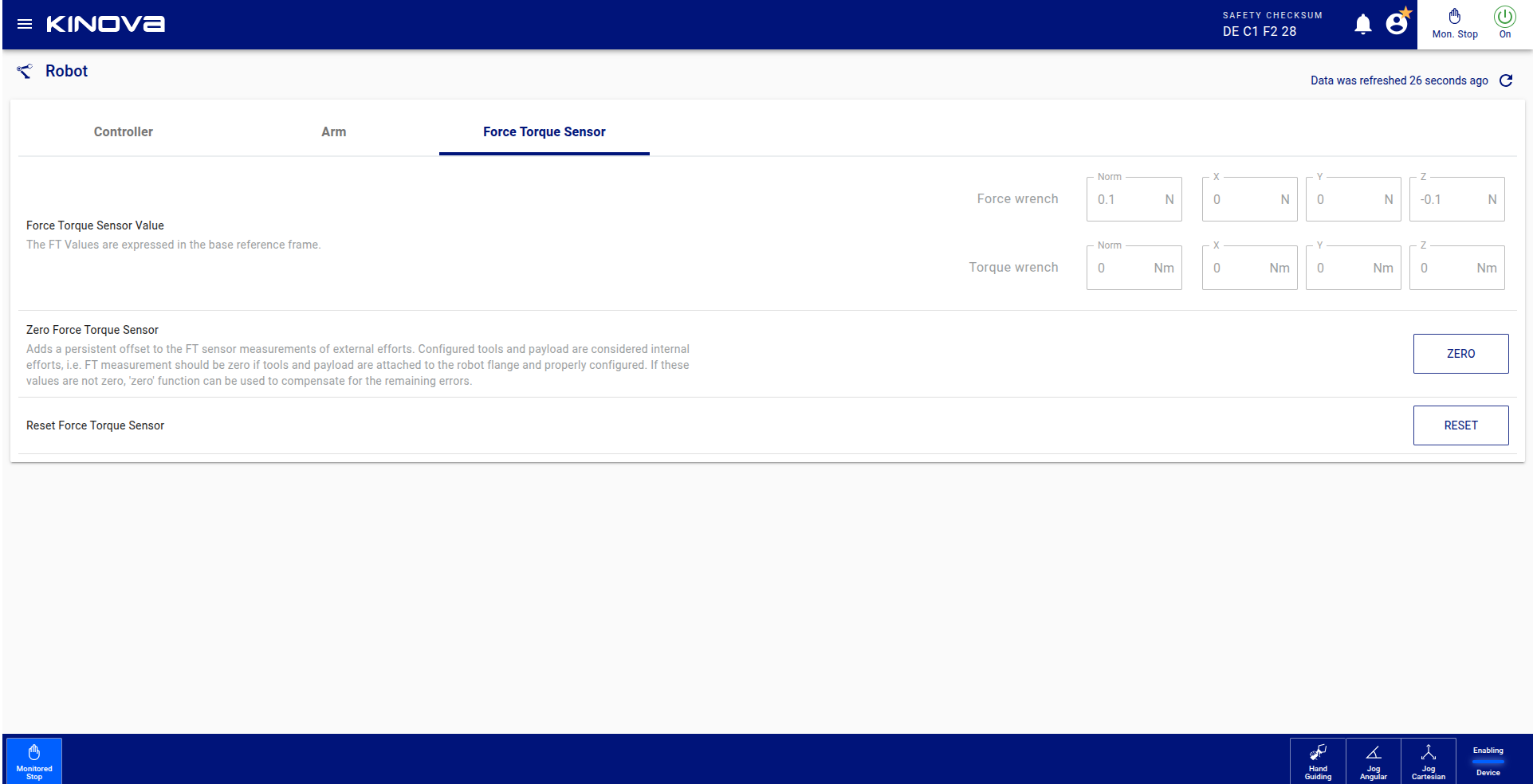

For force/torque, the web app still plays a role. You can zero the sensor from the browser, and the result is immediately visible in RViz:

Fault handling is also exposed through ROS2 services: you can switch operating modes (manual jog, auto, monitored stop, etc.) and clear faults from the ROS side instead of jumping back and forth between terminals and web UIs.

Controllers, Not Just Topics

Instead of pushing everything through one-off topics, the stack uses ROS2 Control:

joint_state_broadcasterpublishes joint positions, velocities, and efforts.joint_velocity_controllerexposes a vector of joint velocities.cartesian_motion_controllerallows smooth end-effector motion via Pose targets.motion_control_handlelets you drag the robot in RViz with an interactive marker.robotiq_gripper_controllercontrols a mounted Robotiq gripper via an action interface.

The idea is to match common patterns in the ROS2 ecosystem so you can plug in your own controllers, planners, or teleop frontends without fighting the hardware layer.

Teleop & Data: SpaceMouse + Vive

Once the ROS2 side was solid, I used it as the base for teleoperation and data collection.

I built two main teleop paths:

- A 3Dconnexion SpaceMouse for smooth Cartesian motion,

- An HTC Vive controller (no headset) for 6-DoF, “point-and-move” style control.

From the Vive controller I read a 3×4 pose matrix:

- The first 3×3 part is a rotation matrix,

- The last column is the position vector.

With a simple calibration step I align the Vive tracking frame to the Link6 base_link, compute delta poses, and send those as end-effector deltas into the driver (on top of the existing joint velocity and twist interfaces).

The SpaceMouse is mapped to end-effector velocities, which the driver converts into commands accepted by Kortex3. Together they give:

A way for a human to “drive” Link6 in a natural way, while I log states + actions into a clean dataset.

Those datasets are what I use later for behavior cloning and a small vision–language–action (VLA) pipeline.

Where’s the Learning?

This project is mostly about infrastructure: ROS2 bringup, controllers, calibration, fault handling, teleop, and logging.

On top of that, I’ve already run:

- a simple behavior cloning model that imitates teleop trajectories, and

- a small VLA pipeline for linking visual context + language prompts to actions.

The details of those models, training setups, and results deserve their own write-up, so I’ll cover the learning side of Link6 in a later blog post. For now, this page is the story of how the cobot went from “low-level API” to a ROS2-native platform for real-world experiments.